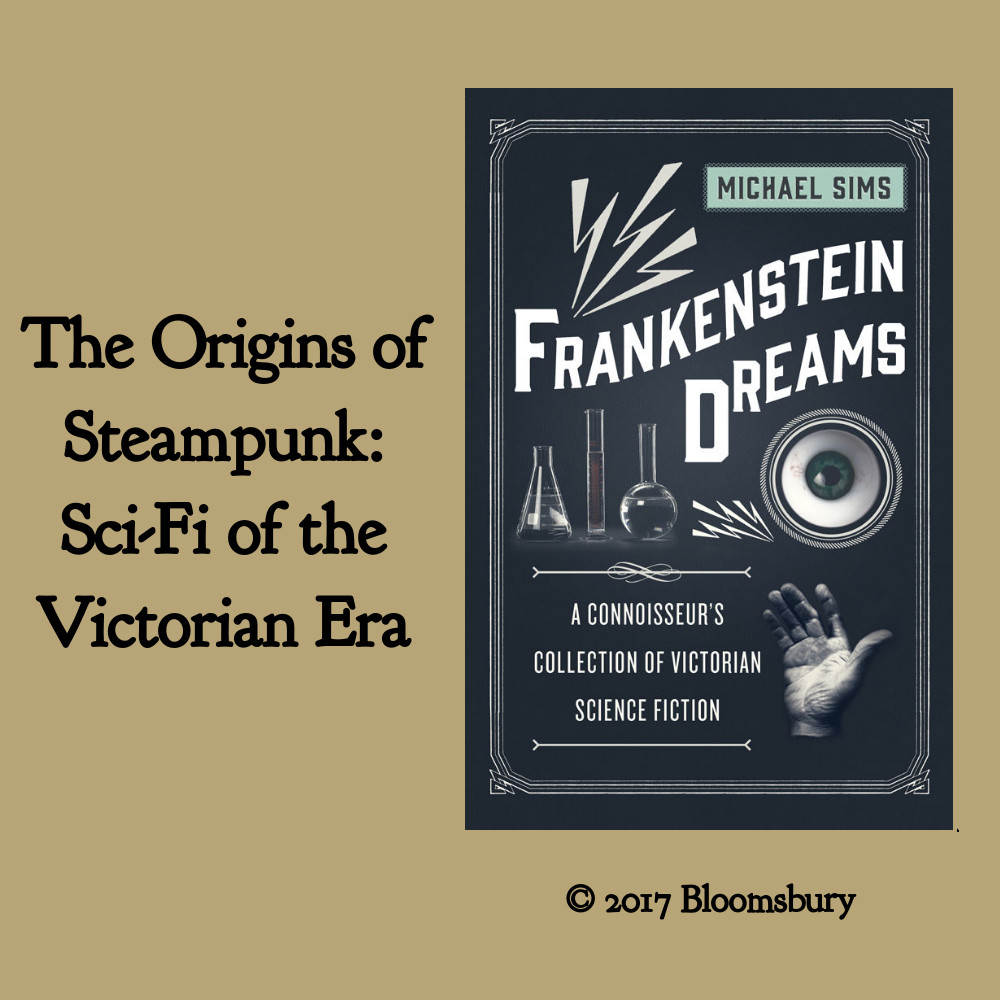

I have a confession to make: Steampunk has been my gateway drug to a wider world of literature. It has gotten me interested in the classics, starting with sci-fi pioneers like Jules Verne and H. G. Wells. Recently as I was browsing in Bookmans (an Arizona retail chain specializing in used books) I came across a volume called Frankenstein Dreams, edited by Michael Sims.

Frankenstein Dreams bills itself as a compendium of the best Victorian-era science fiction. Unlike an earlier collection called Steampunk Prime which I also reviewed on this blog, it contains not just short stories but excerpts from novels. As the title would imply, it features a couple of chapters from Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, which is often credited as being the very first science fiction novel.

Also unlike Steampunk Prime, Frankenstein Dreams contained works by a number of authors who are still well-known to this day, including of course Wells, Verne, and Poe. There are also other literary authors who aren’t currently known for sci-fi: Rudyard Kipling, Arthur Conan-Doyle, and Robert Louis Stevenson. These selections are all stellar and have reinforced my desire to read more Victorian-era classics. Once you become accustomed to the more flowery prose and the somewhat slower pace, you will realize that those people are remembered for good reason: they were masters of their craft. Anyone who complains about “dead white people” in our literary canon is simply jealous that so few modern writers can produce anything that comes close.

Editor Michael Sims also found a number of works by writers who were popular in the past but are currently forgotten. Some are good, some not so good. One particularly good one was “The Hall Bedroom” about a mysterious portrait that turns out to be a portal to another dimension. The weakest was “The Senator’s Daughter” a preachy entry involving a Chinese-inspired movement to ban the consumption of both animals and plants and force people to subsist on nutrient pills. (Was the writer not familiar with the broadly omnivorous diet of most Chinese?) I believe that Sims included this story as an early appearance of specific sci-fi tropes.

It’s interesting to note that several of the authors Sims included were radical activists at the time. One of them, Thomas Higginson, was even a financial supporter of the antebellum terrorist John Brown. (His story “The Monarch of Dreams” was not bad, by the way, except for a glaring plot hole that ruined it for me.) Radicals – in the days be for radicalism was required for college graduation – tend to be interesting people, which may have been why Sims picked them. Or perhaps it was to balance out the inclusion of traditionalist authors such as Kipling who tend to trigger modern “progressives.” Either way, I found the author biographies of both the famous and non-famous contributors to be one of the best features of the book.

Note that I bought the audiobook version of the collection with narration by Tim Campbell. Campbell was among the better narrators I’ve encountered, though some of his foreign accents missed the mark, in particular, a Dutch professor who sounded Russian.

Frankenstein Dreams is an excellent introduction for sci-fi fans, especially steampunks, to the rich variety of science fiction in classic American, British, and French literature. I highly recommend it as an antidote to the “fad of the week” trend in modern publishing. Although some of the included stories are (in my view) sub-par, even those are interesting. I give the book 4.5 out of 5 stars.